9 Things You Probably Didn’t Know About President Pines

His Modest Beginnings, Boyhood Heroes, Futuristic Research and Plans to Tackle ‘Grand Challenges’

By Chris Carroll | Photo by John T. Consoli

The University of Maryland’s new president, Darryll J. Pines, is fond of the concept of “grand challenges”—problems so complex, yet so pressing, that only the full mobilization of scientific, engineering and societal resources will solve them. Think of curing cancer or traveling to Mars.

Pines had begun preparing a slate of them for the university to tackle after he was named the next president in February—and then the world intruded with challenges of its own, as urgent as any that could be devised: a spreading viral pandemic, with more than 175,000 Americans dead as of press time, and the societal pandemic of racism, violence against Black people and institutionalized inequality.

He pivoted, announcing in his inaugural message his plans to direct UMD’s research power at the problems, as well as work to free the campus from the ravages of both pandemics as much as possible.

“The things I wrote about on that first day were not what I would have rolled out in a non-COVID world, or a non-social-unrest world,” he says. “But these are grand challenges facing our society that we must deal with.”

A longtime colleague in the A. James Clark School of Engineering, where Pines landed as an aerospace engineering professor in 1995 and later served 11 years as dean, says Pines would not only guide the school through trying times, but find ways for the university community to excel and grow stronger through them.

“I thought of him as the lemonade dean—when something is going wrong, he asks, ‘How can we find something positive to get out of it?’” says William Fourney, professor emeritus of aerospace engineering. “And he almost always finds a wrinkle where he can make things better.”

Forward momentum, observers say, has characterized Pines’ leadership at UMD so far, whether pushing the Clark School ahead in national rankings, beefing up fundamental undergraduate courses or dramatically increasing numbers of female and underrepresented students and faculty. His devotion to learning beyond the classroom resulted in high-profile wins and world records in student competitions, while his attention to fundraising and donor relations was key to a $219.5 million investment from the A. James & Alice B. Clark Foundation benefitting the entire university.

Those who know him expect Pines to place an array of new grand challenges and opportunities for excellence on the table in coming months for the university to unite behind.

“He likes the big plays,” says C.D. Mote Jr., a longtime mentor of Pines who served as UMD president from 1998 to 2010. “He understands the success of the university is about the people, the vision, the impact. He is always looking to the future, and the students, university, state and nation will all benefit.”

But what about his present and his past? While Pines isn’t known as someone who loves talking about himself (but don’t get him started on the role of engineering in society), he is known for more than just academic and professional achievements—there’s his genuine enjoyment of working with young people, his no-lunch-late-nights work ethic and his easy charm (like showing up in full commencement garb in a neighbor’s yard to help two high school seniors celebrate their virtual graduation). What else might you not know about Pines? Read on for what we discovered.

He’s an identical twin. Darryll Pines is a hair shorter than his brother, Derek, but the two are close enough in appearance that their mother, Maureen Foster Pines (above), a native of England who passed away in 1998, called them “the mirror twins”—particularly apt because Darryll is right-handed and Derek is left-handed. Both have the engineering knack; Derek, an electrical engineer, is vice president at Parsons Corp., a transportation and defense technology consulting firm. Because the two live on opposite coasts, the chance of Pines double vision (or, perhaps, identity-trading hijinks) around College Park is low.

A boyhood encounter with a Tuskegee Airman helped set his path. The deep racial inequality in America that came under greater scrutiny after the May killing of George Floyd was everyday reality for a young Darryll Pines. He grew up in a working-class home in East Oakland, Calif., a majority Black and relatively impoverished part of the San Francisco Bay Area where opportunities were scarce and “university president” was not the expected career. But at a junior high summer camp for aspiring pilots, he met one of the Tuskegee Airmen, the famed group of Black World War II aviators who shot down racist myths along with German fighter planes. It helped the 13-year-old Pines envision what he was capable of. “I’ll never forget what this pilot told me about a whole bunch of African Americans who helped win the war,” Pines says.

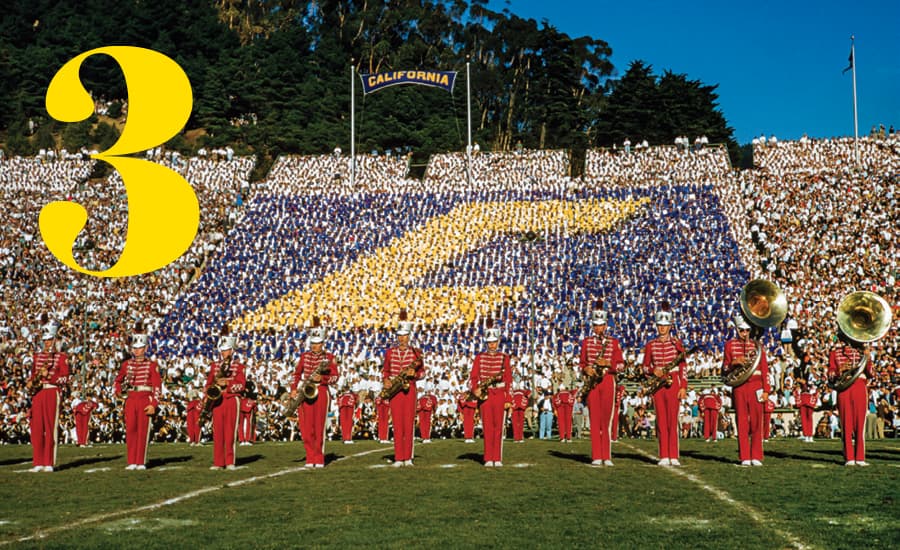

He went to a top college near home—and wants more Prince George’s County students to have the same opportunity. Pines’ parents didn’t have a chance for higher education, but worked ceaselessly to make sure their children did. Still, without a need-based scholarship (followed by merit awards), his undergraduate education at the nearby University of California, Berkeley would have been impossible. He wants students from places like Prince George’s County and Baltimore, which remind him of his hardscrabble hometown, to have similar chances. “I think the purpose of a public land-grant institution is to afford an equal opportunity for everyone in the state to get an education, and to move their family from one side of the economic scale to the other,” he says.

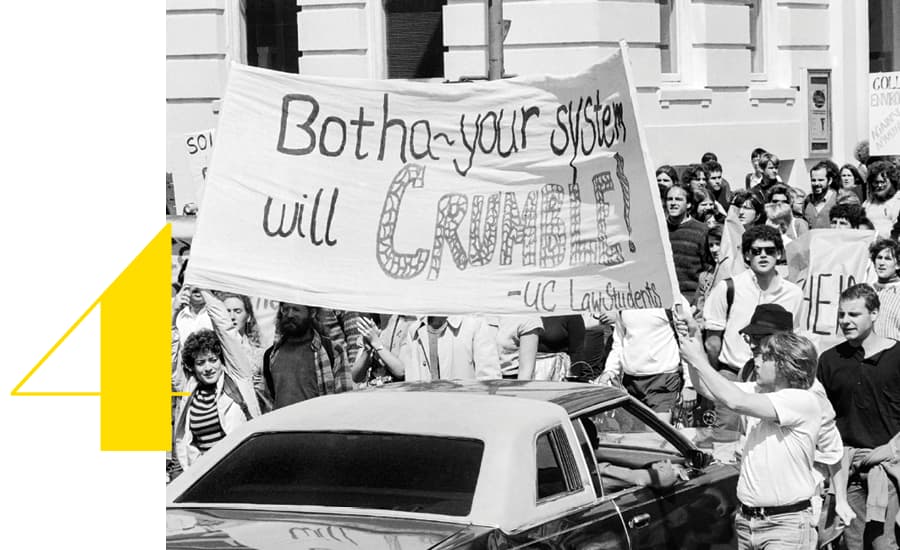

He was a student activist. Pines’ eyes were opened to institutionalized injustice at Berkeley, where he participated in protests on its famed Sproul Plaza. His passion was American divestment from apartheid South Africa, which was holding dissident Nelson Mandela prisoner. Seeing Mandela in person a few years later in 1990 in Boston, while Pines studied for his doctorate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and South Africa inched toward democracy, ranks as a highlight of his life.

He managed “gee-whiz” projects at DARPA, the agency that invented the internet. An expert in spacecraft control and navigation, Pines took it to the next level during a 2003-06 leave of absence from UMD. Working at the famed Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency—credited for innovations ranging from computer mice to GPS to the internet—he oversaw exotic aerospace projects like the development of tiny, hummingbird-like aircraft.

A former UMD president mentored him in college (and he later returned the favor). Mote met Pines while the young man was attending Berkeley High School and was later Pines’ undergraduate adviser in the mechanical engineering department at UC Berkeley. In 1998, when Mote became UMD president, Pines (who arrived at the university in 1995) was the only person the lifelong Californian knew on campus, and helped the new president get his bearings. “I went right to him, past all the department chairs and all the deans and straight to this assistant professor I had not seen since 1986,” Mote says.

He has a high-achieving family. Pines and his wife, Sylvia, have two Terp children—Kalala ’18, pursuing a doctorate in physical therapy at Emory University, and Donovan, a 6-foot-5 defender for D.C. United. He was named to the All-Big Ten First Team as part of UMD’s national championship-winning men’s team during his junior season in 2018. Although he went pro before graduating, he continues knocking off roughly a course each semester on his way to a biological sciences degree. Pines’ older sister Denise is a former head of the Medical Board of California, an entrepreneur and a social activist for Black women and girls. His father, Claude, served four years in the U.S. Air Force in England (where he met Pines’ mother), returning to the Bay Area to work blue-collar jobs at Sears and Pfizer. He later earned an associate’s degree in management and worked for over 20 years as an analyst for the Navy.

Student competitions get him revved up. Pines’ easy rapport with students was evident as Clark School dean when, mic in hand, he led cheers at the annual Alumni Cup competition between departments or mingled with members of the Terps Racing squad. Mote chalks it up to a healthy competitive nature, plus watching MIT’s successful teams, like one that flew the Daedalus aircraft to the distance record for human-powered flight in 1988. At UMD, Pines championed another aircraft team—Gamera—that competed for the $250,000 Sikorsky Prize and holds the world record for longest human-powered rotorcraft flight. Sheron Williams, longtime Clark School assistant to the dean, remembers accompanying Pines to the announcement of the 2011 U.S. Department of Energy’s Solar Decathlon winner on the National Mall. When UMD’s entrant into the contest for a self-powered house, Watershed, won, “He was absolutely giddy for the students,” Williams says. “He was beside himself.”

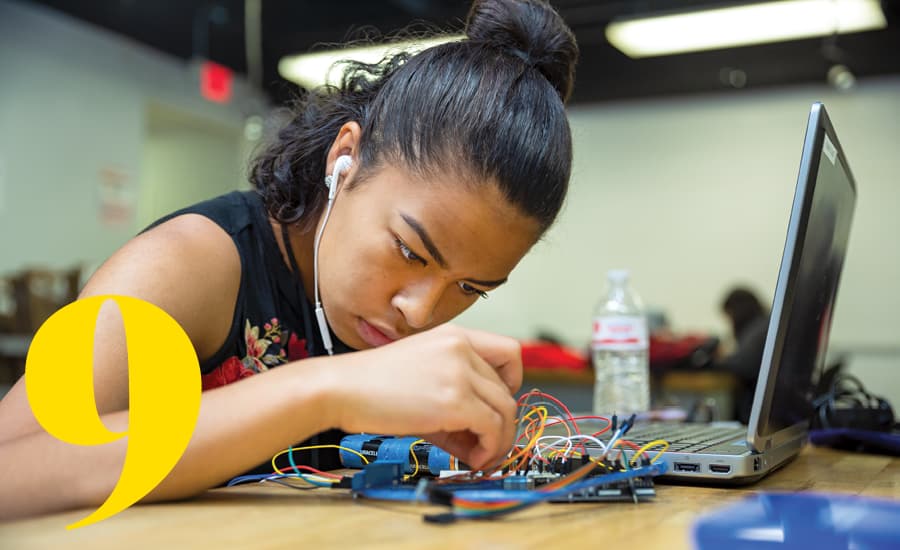

He’s the driving force in the U.S. to get high schoolers AP-like college credit for engineering classes. Engineering is one of the key disciplines of recent centuries. So why are there relatively few opportunities to study it before college, Pines wonders—and why can’t high schoolers earn college credit like students taking Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate tests in subjects from physics to literature? To close that gap, Pines is leading a nationwide pilot project, Engineering for Us All (E4USA), to implement a curriculum accessible to students from a wide range of socioeconomic and academic backgrounds—math genius not required.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply

* indicates a required field