D.C. History by the Forkful

Anthropology Alum’s Food Tour Dishes Out Tales From ‘Black Broadway,’ Taste of Immigrant Culinary Traditions

By Karen Shih ’09

Photos by Stephanie S. Cordle

Bellies full of D.C.’s most famous hot dog—a half-smoke smothered in chili, to be exact—we were dutifully following our tour guide down U Street when he halted in the middle of a block.

I glanced around the alleyway: trash and recycling bins, overgrown weeds, a car or two, nothing remarkable. Scaffolding stretched between the buildings on either side of us, offering a little shade from the midday sun.

Then our guide told us why we were there. Fifty percent of D.C.’s Black population once lived in alleys like this one, he said. Originally constructed for horse and carriage storage, they ended up crowded with makeshift housing, sheltering entire communities during the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Today, the area is largely gentrified—yoga mat-toting residents who glanced curiously as they walked by made that clear—but longstanding businesses harken back to D.C.’s past. Partially obscured by the scaffolding is a mural of tropical blooms and a portrait of William and Winifred Lee, who founded Lee’s Flower Shop around the corner in 1945, thanks to a loan from the city’s only Black-owned bank. The couple then invested in other Black entrepreneurs, helping to bolster “Black Broadway,” an epicenter for African American music, culture and activism that drew the likes of jazz legend Louis Armstrong and author Zora Neale Hurston from the 1920s to 1950s.

Mural of William and Winifred Lee, who founded Lee’s Flower Shop on U Street in 1945

For what was billed as a three-hour foodie excursion, it was unusually deep content. But that’s the goal of Blue Fern Travel’s Fork Tours, co-created by Stefan Woehlke M.A. ’13, Ph.D. ’21 and his wife, Mary Collins. They aim not only to fill stomachs with some of the most iconic bites in the nation’s capital, but to fill minds with its often-overlooked history.

“Washington, D.C., has a very unusual tourism market because people come to learn a national story, to see the monuments and the Capitol and the White House, not to learn about D.C.,” says Woehlke (below). “But tourists need to eat, and we realized food tours could be a way to get people into neighborhoods they wouldn’t otherwise visit.”

The company that Woehlke co-founded while pursuing his doctorate in anthropology at UMD now employs a small coterie of guides and supports a local food bank while leading eager visitors through three neighborhoods.

“Having a food tour allows you to bring people in and let their guard down and be more receptive to hearing stories about the past, especially diverse histories,” he says.

“We realized food tours could be a way to get people into neighborhoods they wouldn’t otherwise visit.”

Stefan Woehlke M.A. ’13, Ph.D. ’21, co-creator of Blue Ferm Travel’s Fork Tours

Woehlke isn’t Indiana Jones. He’s mild-mannered where Indy was gruff, and a family man with three young kids where Indy was a womanizer. But he briefly considered following the fictional whip-cracking archaeologist’s path into Central American jungles to study Mesoamerican civilizations.

Stefan Woehlke

A short research stint in Belize during college snapped him out of his swashbuckling dreams. “It felt kind of too disconnected from the challenges the world is facing,” Woehlke says, such as racism, sexism and economic inequality.

He switched his focus to the colonial period through the 20th century, in particular revealing the untold stories of African Americans who persevered through enslavement, discrimination and segregation. After earning his bachelor’s degree from George Mason, he spent the bulk of his time at fourth President James Madison’s home, Montpelier, where he researched the lives of the African Americans who were enslaved there, as well as how they and their descendants navigated the transition to post-Civil War freedom.

As he continued his research on this—the subject of his dissertation—he discovered he also wanted to spread his love of history to different audiences, and that the love of food he shared with his wife could be the link.

“We realized when we connected with local communities (in our travels), it was always over a meal,” he says, such as a red snapper speared by a neighbor as a welcome gift in the Virgin Islands or a lively backyard asado (barbecue) that helped travelers surmount language barriers in Chile.

Collins took a business pitch to a local competition and won the $500 people’s choice award, which they used to start the company in 2014.

In the early days, Woehlke wanted to pack in so much history and try so many dishes that the tours stretched nearly five hours, with tastes at eight restaurants. “People got a lot for their money, but some guests couldn’t keep up,” he says.

Today, they’ve halved the number of stops and walk less than two miles over three hours, which allows guests to enjoy bigger portions and time to digest between savory dishes and dessert on their tours in Old Town Alexandria, Georgetown and U Street—the first one they launched, and still their most popular today.

Kamal Ali, one of the co-owners of Ben’s Chili Bowl and son of founders Ben and Virginia, flips sausages on the grill.

Just a year after D.C. became the country’s first majority-Black big city, Trinidadian immigrant Ben Ali and his fiancée, Virginia, opened Ben’s Chili Bowl on bustling U Street in 1958, introducing to the community what was, by the standards of the time, a spicy concoction. Patrons included Martin Luther King Jr., who set up an office just down the street; jazz legends Ella Fitzgerald and Duke Ellington, who performed at clubs nearby; and students and faculty from historically Black Howard University, half a mile away.

This was near the end of U Street’s heyday as Black Broadway. Since the late 19th century, Jim Crow laws and segregation had pushed Black intellectuals, artists and entrepreneurs to develop separate areas where they could live and thrive. In that era, U Street’s Black-owned banks, shops and clubs were born.

D.C.’s robust Black population stemmed in part from Camp Barker, set

up during the Civil War to hold enslaved people who were considered

contraband from the South. When President Abraham Lincoln signed the

Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, many of them chose to stay and forge a

new life in D.C., building homes to create the beginnings of U Street.

(To be sure, Black people have lived in what’s now D.C. since before the

nation’s founding, and enslaved people helped build the White House,

the Capitol and other iconic buildings that tourists flock to today.)

In the 1960s, African American civil rights activists gathered at Ben’s Chili Bowl. And when King was assassinated in April 1968, U Street fell victim to racial riots. Protesters burned down business after business, though they spared Ben’s, which went on to feed activists and first responders alike.

The area fell into disrepair after that, but through the decades, even as the crack cocaine epidemic spread and construction of the Metro’s Green Line blocked the street, Ben’s remained. The subway line opened, and luxury apartments and trendy restaurants started popping up—part of the gentrification of D.C., as the Black population shrank from more than 70% during its “Chocolate City” days to just 45% today. But Ben’s remained, and even expanded to Ben’s Next Door (yes, literally next door), offering a more upscale dining experience.

It was that “remarkable continuity” that prompted Woehlke and Collins to approach the Ali family. The concept of a food tour was so new in D.C. that the Blue Fern founders were initially turned down at other restaurants when they pitched their idea—but when Ben’s co-owner Nizam Ali (son of the founders) agreed to work with them, more doors opened.

“They do a really good job of telling this rich history. ... D.C. isn’t about the federal buildings. It’s about the people, the culture, the music.”

Nizam Ali, co-owner of Ben’s Chili Bowl

“They do a really good job of telling this rich history,” Ali says. “We feel it’s our role, being this anchor here on U Street, to teach people about Black Broadway. D.C. isn’t about the federal buildings. It’s about the people, the culture, the music.”

That’s what Woehlke focuses on as he designs the tours, drawing on UMD sociology Distinguished University Professor Emerita Patricia Hill Collins’ lessons on intersectionality. He hopes that compelling storytelling will help guests find common threads with people who have different backgrounds and experiences.

Blue Fern’s approach has detractors; a handful of online reviewers dislike the history-focused approach, and a few prospective tour guides have turned down the gig over the “progressive” nature of the content.

That’s exactly the attitude he’s trying to change. “Animosity in society is connected to ignorance,” Woehlke says. As a white man, he knows he’s not the ideal person to tell stories about Black history. But he hopes that giving his mostly white customers an easy entrée into that past through food will inspire them to take a closer look at how similar issues—discrimination, immigration, gentrification—affect their own towns, and to seek out other Black- or immigrant-owned businesses back home too.

“We’re aiming for a broader impact than just having a nice afternoon and eating some good food,” he says.

A vegetarian injera platter from Dukem, featuring stewed collard greens, cabbage and potatoes, spicy lentils and tomato salad.

We kicked off our tour with the signature dish of D.C., a chili half-smoke (a half-beef, half-pork sausage) that President Barack Obama stopped by to try just before he was inaugurated.

“The half-smoke has a fantastic snap—it bites back as you bite into it,” said guide Jim Haefele.

Our next stop, at Ethiopian restaurant Dukem, offered a vegetarian

counterpoint to the meat-on-meat starter: a platter of stews and salads

over sour injera flatbread, as well as lentil sambusas, fried triangular pastries.

The Ethiopian community in the D.C. metro area is the largest in the world outside of Ethiopia, Haefele said, thanks to a wave of immigration following the Communist takeover in 1974. At the time, D.C. property prices had plummeted due to the recent riots, so the new residents were able to easily buy up homes and businesses, putting down roots and offering a lifeline to family and friends hoping to escape the violence in their homeland.

After we had our fill, Haefele excused himself to go pay—always full price and with a tip, following Blue Fern’s ethos of supporting small, locally owned businesses. It’s unusual in the food tour industry, where companies often haggle for a group discount. Since they launched Blue Fern, they’ve spent a half-million dollars at these restaurants.

They also donate a portion of each ticket sold to Bread for the City, a nonprofit that provides food, clothing and social services to D.C. residents in need, enabling the organization to feed a person for a day. Blue Fern Travel has donated over 35,000 meals since its founding.

That’s something Woehlke and his wife are proud of. “Tourism brings a

lot of money and moves a lot of money around the globe. But it doesn’t

really go into the communities where people are living,” he says.

“That’s why we decided to open a social enterprise that supports the

community.”

A busy Saturday morning at the colorful Colada Shop.

Today, Woehlke juggles his work as a postdoctoral associate at UMD, managing the Historic Preservation Archaeology Lab and teaching undergrads about 3D documentation, with his ambitious plans for growing Blue Fern. In 2022, the company surpassed its pre-pandemic tour numbers and is now looking to offer drink-based excursions, as well as expand to Baltimore.

They also acquired a global tour company last year called Far Horizons, which offers international multi-day trips led by archaeologists and other scholars with access to behind-the-scenes digs and backroom museum collections.

A scoop of roasted barley, a Lunar New Year special from Ice Cream Jubilee

Closer to home, we stopped at our last two restaurants for a duo of desserts: a scoop each from Ice Cream Jubilee, where I got the roasted barley flavor, a nod to creator Victoria Lai’s Chinese heritage, and a warm pastelito from the Colada Shop—a pocket-sized ode to immigrant founder Daniella Senior’s roots in the Caribbean.

As Haefele handed us the pastries, he asked if we could tell what was inside. I crunched into the flaky square, and a pink jam came oozing out. It had a slightly tart flavor, almost like a pear, but with a tropical twist: guava, Haefele told us.

It wasn’t what any of us expected. But like the eye-opening history we learned on the tour, it was a refreshing taste of something new. TERP

Tidbits From the Tour

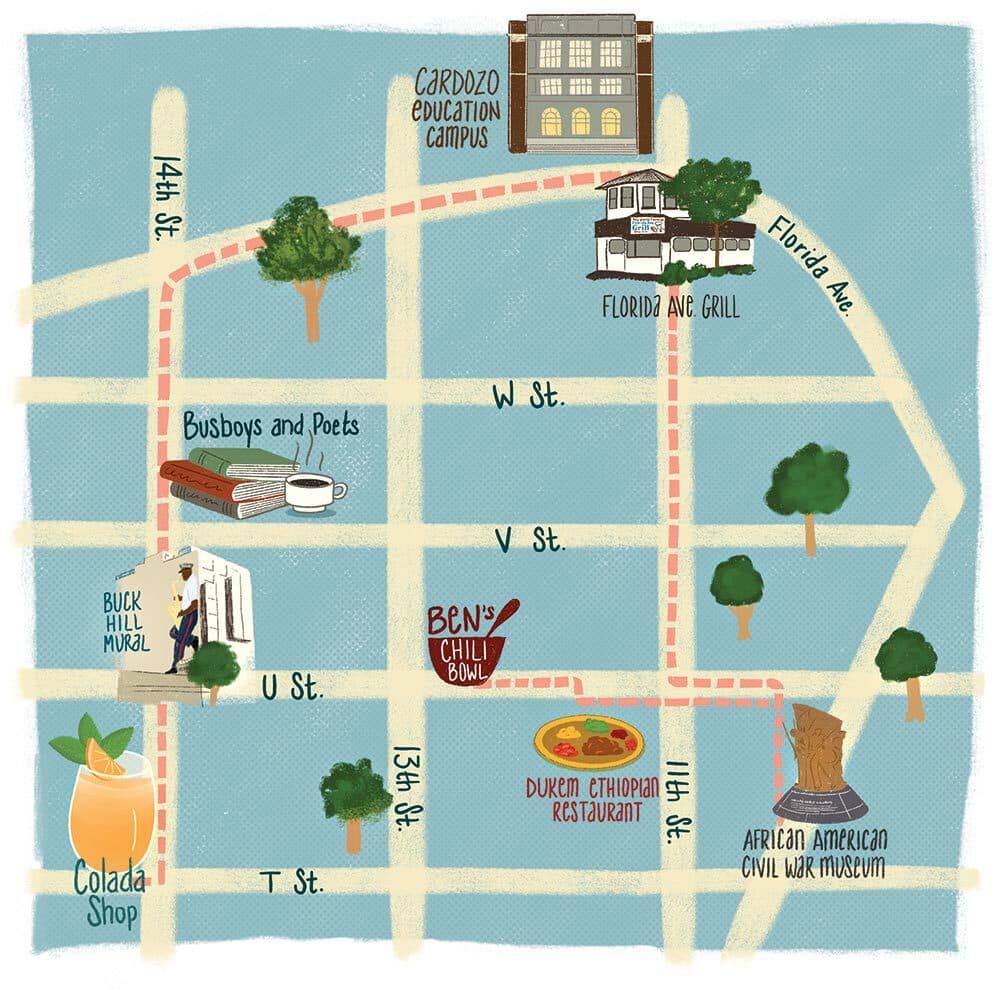

Map by Valerie Morgan

BEN’S CHILI BOWL: A massive mural celebrates Black politicians and celebrities including longtime U.S. Rep. Eleanor Holmes Norton and former D.C. Mayor Marion Barry, as well as Prince and Muhammad Ali—all of whom have eaten at Ben’s.

DUKEM: “The injera is a food and napkin and utensil, all at the same time,” says Haefele, who lived in Ethiopia for several years. He often saw restaurants in Addis Ababa with signs that said: “Visit our sister restaurant in Washington, D.C.”

AFRICAN AMERICAN CIVIL WAR MEMORIAL: The walls surrounding the statue feature nearly 210,000 names, honoring people of color who fought for the Union Army.

THE FLORIDA AVENUE GRILL: The nation’s oldest continuously operating soul food restaurant once had margins so thin that “they operated two chickens at a time,” says Woehlke. They butchered and fried up the first two in the morning, and only bought more once those were sold.

FRANCIS L. CARDOZO EDUCATION CAMPUS: The massive gothic building, known as the “castle on the hill,” was built in 1917. Today, it enrolls 800 middle and high school students, far less than its capacity of 1,100, as a result of white flight from D.C. Public Schools.

BUCK HILL MURAL: The 70-foot-tall painting honors the mailman and jazz musician who played in U Street clubs with the likes of Miles Davis.

THE COLADA SHOP: The colorful café evokes pre-revolutionary Cuba. Founder Daniella Senior says she sought out the diverse neighborhood. “This area represents such a beautiful array of different cultures, and I’m proud to be a part of that.”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply

* indicates a required field