Animal Instincts

From left: Smith examines 2-month-old Bao Bao; 8-month-old Bao Bao plays with Mei Xiang in the outdoor enclosure.

Alum Champions Conservation Through Work at National Zoo

By Karen Shih ’09

Photo Courtesy of Courtney Janney and Abby Wood of the Smithsonian’s National Zoo

This story is from the Fall 2015 issue of Terp Magazine. Brandie Smith is now the Director of the Smithsonian's National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute, overseeing the entire operation. As the pandas prepare to return to China in mid-November 2023, learn how she led reproductive efforts for years.

Each morning, before the curious foreign tourists, jaded local joggers or screaming school groups pour into the Smithsonian’s National Zoo, Bao Bao the panda starts her day by crunching soy protein biscuits and sucking on a bottle of honey water.

It’s not just a leisurely breakfast. Zookeepers toss the little red biscuits to catch the attention of the 2-year-old as she ambles through a series of metal enclosures that take her from the indoor sleeping quarters to the outdoor habitat. She stuffs them into the corner of her mouth to chew like bamboo, stopping every so often so the keepers can weigh her, simulate drawing blood and have her practice lying down for future ultrasounds.

Bao Bao isn’t just an adorable member of the zoo community. Like the twin cubs born there Aug. 22, she’s part of a global effort to save the endangered species. And the odds were stacked against her being here today.

Just ask Brandie Smith Ph.D. ’10.

A year before Bao Bao was born, her mother, Mei Xiang, suddenly abandoned a week-old cub, which turned out to have had unseen developmental issues. Smith, then the curator of giant pandas, had to make the devastating call to have the cub declared dead after veterinarians were unable to revive it.

Even today, with a happy, healthy Bao Bao, Smith still wells up thinking about it.

“It’s scary to work with these animals and have zero margin for error,” she says. When they’re born, “it’s exciting but terrifying because you know nothing can go wrong. Everything has to be 100 percent perfect all the time.”

Now, as the associate director for animal care sciences, she’s responsible not only for the care and management of a wide variety of animals, from elephants and great apes to birds and reptiles, but also for research to ensure these species thrive in both captivity and their natural habitats.

“These animals are ambassadors for their wild counterparts,” she says. “We have groups of the best scientists in the world who are working to save these species in the wild.”

DREAMS VS. REALITY

“Most people grow out of their childish dreams,” Smith says. “I didn’t.”

As a kid, she was fascinated by big cats, particularly jaguars, and unusual Australian wildlife like the Tasmanian devil. Her family lived in western Pennsylvania, within driving distance of the National Zoo in D.C., SeaWorld Ohio and the Pittsburgh Zoo, which they visited often.

She studied biology at Indiana University of Pennsylvania, then zoology at Clemson University, thinking that would get her into a zoo.

“I had a master’s degree, two internships, and I couldn’t get a job,” she says. “I was living in my sister’s basement in Boston, volunteering at the zoo there and working as a waitress to earn money.”

Then came a job offer: keeper of cheetahs and rhinos at the Dallas Zoo. The catch? It was a temporary position paying minimum wage—in a city she’d never visited and where she knew no one.

Of course, she took it. “Most zoo people have a story like that,” she says. “There are more people who want to work in zoos than there are jobs. Once you prove you can work in the freezing cold and raging heat and don’t mind shoveling poop, you’re in.”

She still has a picture of Indy, a black rhino in Dallas, on her wall today. “I remember being amazed at how an animal so big and potentially dangerous could be so gentle,” she says. “He used to love to come up to the bars, lean in, and have the side of his face rubbed or his back scratched. The side of his face was soft, like velvet.”

After a year in the blazing Texas sun, she found an opportunity with the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) in Maryland as a conservation biologist, where she could work on a larger scope. Over the next decade, she visited almost every zoo in the country and others worldwide, and was promoted several times.

Then she started feeling an itch: “I kept thinking, ‘I want to go back to a zoo.’ I wanted to be back on the ground, working with animals.”

ACHIEVING THE IMPOSSIBLE

To work with pandas, your personality has to mirror a panda’s: calm, thoughtful and deliberate.

But beneath the panda team’s mellow exterior hides the collective determination that brought Bao Bao into the world.

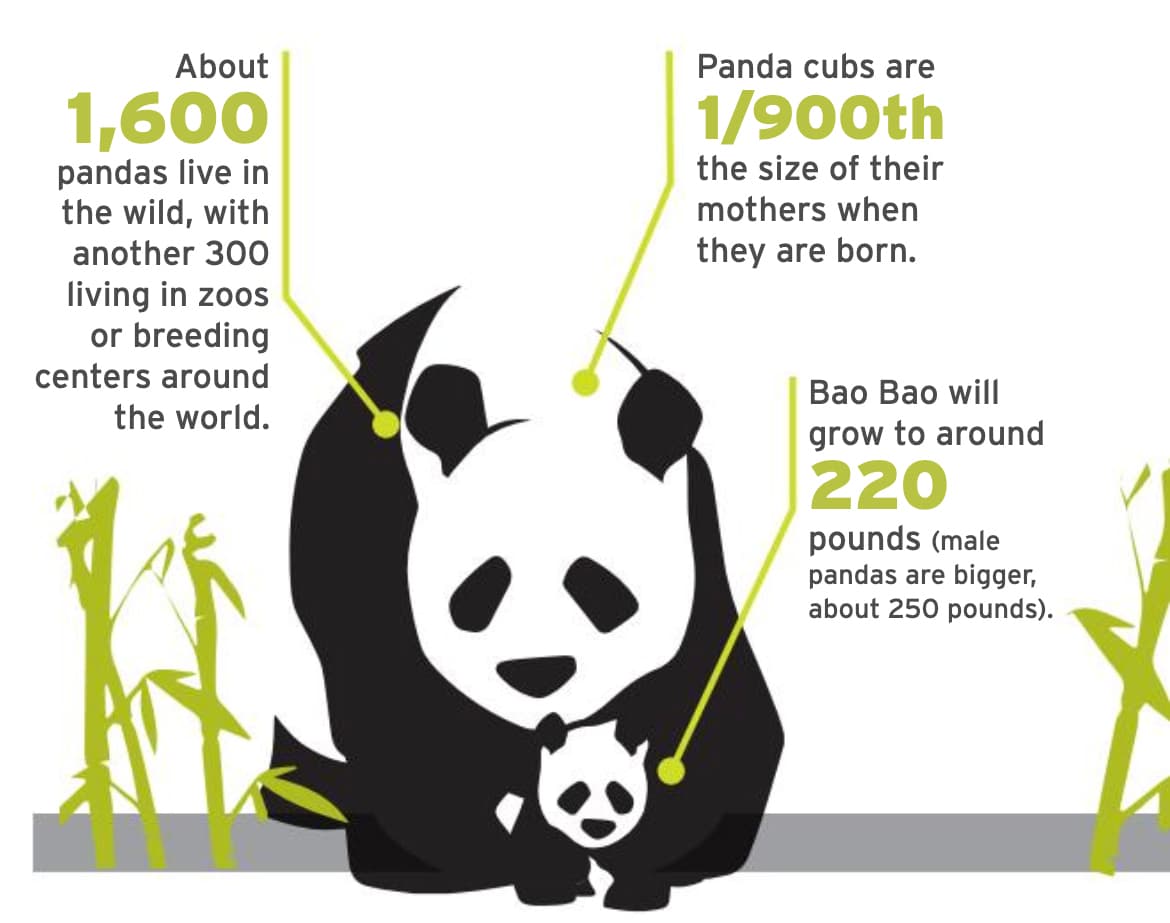

Just 1,600 of these endangered animals are left in the wild because of hunting and deforestation—pandas need to eat 20 to 40 pounds of bamboo each day—so studying the 300 or so in captivity is important for maintaining and growing the population. Even with human support, however, pandas reproduce slowly: Females are sexually mature from around 4 to 20 years old, but they usually only have one cub at a time, and there’s at least a two-year gap between each cub (they must be weaned first).

At the National Zoo, the panda team tried for years to get Mei Xiang pregnant after she weaned Tai Shan, her first cub, in 2006. He was sent to China in 2010 (as part of the National Zoo’s panda loan agreement), and two years later, Mei Xiang finally gave birth—but that cub died at just a week old.

By 2013, “everyone in the zoo, everyone in China had given up,” says Smith. She had jumped at the opportunity to work at the National Zoo in 2008, which put her in charge of all mammal curators.

The panda curator soon retired, thrusting her into the day-to-day operations of the panda house on top of her regular duties. She oversaw the 10-person team that not only cares for the pandas, hauling hundreds of pounds of bamboo daily and introducing enrichment materials like mulch and hay, but also works to get Mei Xiang pregnant.

“Statistically, Mei Xiang had less than a 5 percent chance of having a cub, given her age [15] and the interbirth interval,” Smith says.

Panda pregnancy is a tricky thing. For one, Mei Xiang and Tian Tian, the zoo’s male panda, have never been able to produce a cub the natural way (it’s tough with only a two-day window each year to try), so artificial insemination is always necessary with this pair. After that, the pregnancy isn’t easy, either.

“The trouble with pandas is that there are two parts to their gestation,” explains panda keeper Marty Dearie ’97. A fertilized egg can float around the uterus for three to four months before implanting, which then starts the 40- to 50-day gestation period. Female pandas also experience pseudo pregnancies, during which they go through hormonal changes, build nests, eat and drink less and become more sedentary.

None of Mei Xiang’s pregnancies ever showed up on the ultrasound, so “we pretty much know it’s a pregnancy when she has the cub,” Smith says.

On Aug. 23, 2013, much to the surprise and joy of Smith, her team and panda fans everywhere, Bao Bao emerged, looking more like a naked mole rat than a bear (save for the thin layer of white fuzz).

“We had achieved the impossible—and that was the most adorable panda cub you could imagine in your entire life,” Smith says.

The team was more hands-on with Bao Bao than the cub that died and examined her just days after she was born, taking cues from their Chinese colleagues (an approach Dearie credits to Smith’s open-mindedness). They closed off the panda house for months while staffing it 24 hours a day.

That brought the already tight-knit crew even closer. The members consider each other family, says biologist Laurie Thompson, who jokes that Smith plays the role of “Mom.” “She’s very good about the work-life balance,” Thompson says, and made sure the team members always rotated and went home to see their kids.

Staying grounded was important during that frenzied time, when media descended on the zoo for any nugget of news, and the public overwhelmed the online panda cams and voted by the thousands to choose the cub’s name.

“While most of the comments were positive, people will say we’re doing bad things,” Smith says. “You have to block that out. There were some pretty brutal comments when we were weaning Bao Bao. They said Mei Xiang was a bad mother and that we were going to hurt the cub.”

But for Smith, all of that faded away with the joy of watching Bao Bao open her eyes for the first time, climbing on her mom’s back and rolling down the hills of the outdoor enclosure. Balancing roles as a scientist, educator to the public and international liaison to China, she says, has made working with pandas “maybe my most fun job.”

SAVING SPECIES

Of course, Bao Bao isn’t the only baby Smith and her zoo colleagues have brought into the world. On any given day, you can see lion cubs pouncing on each other or a sloth bear cub wrestle his dad.

“If you see a pair of animals [at the zoo], someone has made a scientific decision that they should be together,” says Jon Ballou Ph.D. ’95, senior research scientist at the National Zoo and one of Smith’s doctoral advisers.

“Brandie represents the kind of curators that are really needed,” says Ballou, who oversees the global panda breeding program and advises government agencies on species including the California condor. She’s “concerned about the broader issues of designing good scientific breeding programs not only for the animals at her own zoo, but all animals at all zoos.”

Ballou and professor emeritus Jim Dietz, both part of the Behavior, Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics (BEES) Program at UMD, advised and supported Smith during her long journey to earn her doctorate. During that decade, she married and had two children, now 9 and 11, while juggling increased responsibilities at AZA, then the zoo.

Her research focused on animals that live in large groups. Scientists have a good grasp on how to maintain wild genetic representation and avoid inbreeding in animals with known pedigrees, Smith says, but “what do you do with a tank of fish? A flock of flamingos? A herd of antelope?”

Tagging each animal and encouraging certain ones to mate is difficult, since animals in those settings tend to do better when given choices. She modeled different ways of plucking animals from different groups at certain intervals to maintain diversity and decrease individual tagging.

Her research is just one example of the knowledge and methods that can be used both in zoos and in the wild to save thousands of species facing threats like habitat loss and poaching. Soon, she’ll create opportunities for the next generation of scientists.

“My advisers inspired me to think beyond just getting a degree, to the bigger meaning of what I was studying and how it could be used,” she says. Just months into her current position, she’s planning to work with the UMD Sustainable Development and Conservation Biology graduate program, so master’s students can research at the zoo.

THE FUTURE TAKES FLIGHT

As Bao Bao contentedly gnaws on bamboo in front of a crowd of cooing fans, she has no idea her time as panda poobah is coming to an end.

Members of the panda team traveled to China this spring to get sperm from a different male—Tian Tian has many siblings, so he isn’t particularly valuable genetically—and they inseminated Mei Xiang with both of their sperm in late April.

“Every other year, people didn’t expect her to get pregnant,” Smith says. “It was almost like buying a lottery ticket. Now they think, ‘You’re going to give us twins this year, right?’”

The public's optimism was rewarded: Just a day before Bao Bao's second birthday, Mei Xiang gave birth to two cubs. The smaller one died four days later, despite the panda team's round-the-clock efforts. The surviving cub is male, and genetic testing determined he is Tian Tian's sons.

Since Smith’s promotion earlier this year, the day-to-day efforts at the panda house are out of her hands. She’s taking on larger projects, like the multiyear transformation of the elephant habitat, for which she negotiated the acquisition of four Asian elephants to increase the herd to seven. Now she’s working to overhaul the Bird House to create the first major exhibit about North American migratory birds in an American zoo.

“There are amazing, spectacular birds in our back yards,” she says. “How do we make this big story accessible to the people who come here to the zoo? How can they help us conserve them?”

The National Zoo has more opportunities than most to reach the public, since admission is free for its more than 2 million annual visitors. That accessibility makes her long hours—she usually arrives by 7 a.m. and doesn’t leave until 6 p.m. and is on call during evenings and weekends—all worth it.

“I love it because anyone from any walk of life can come through our gates,” Smith says. “It’s such a magical thing when you see these animals and start to appreciate them.” TERP

0 Comments

Leave a Reply

* indicates a required field