Last Words

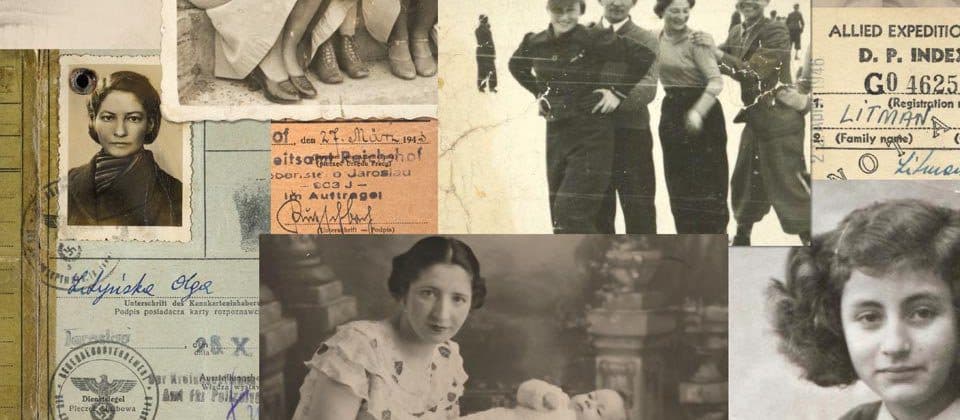

For Two Decades, a UMD Professor Has Led a Writing Workshop for Holocaust Survivors. Seventy-six Years After World War II’s End, Their Task Has an Urgency Both Personal and Public.

By Sala Levin ’10 | Photos courtesy of U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum CollectionIN 1964, Peter Gorog and a few friends hitchhiked from the southern border of their native Hungary some 800 miles north to the Baltic Sea. Along the way, they passed through Warsaw, where a monument commemorated the 1943 ghetto uprising. Gorog wanted to stop there. It was the closest thing he could imagine to a gravesite for his father.

Born in Budapest in 1941, Gorog was the son of Olga, a hatmaker, and Arpad, an office manager.

“It wasn’t a good place to be born in a Jewish family,” says Gorog. During Olga’s pregnancy, Arpad was conscripted into forced labor, and was allowed to meet his son only for a short time three months after his birth. In 1942, Arpad was sent to Ukraine. The Hungarian Ministry of Defense declared him dead in January 1943.

Twenty-one years later, Gorog sneaked out early one morning in Warsaw to stand before the 36-foot stone wall depicting the leaders of the uprising emerging in bronze. There, free from the state-mandated forgetting imposed by formerly German-allied Hungary, he felt a connection to the man he never knew. “That was the first time I related to the Holocaust and to what happened to the Jewish people and personally to my father.”

Yet even after he defected from socialist Hungary to the United States in 1980 and began talking about his wartime experiences—from living in a protected apartment purchased by Swedish architect and humanitarian Raoul Wallenberg to being liberated from the Budapest ghetto in 1945—his memories of that morning in Warsaw remained buried. What shook them loose decades later was a prompt handed out in a writing workshop run by a University of Maryland faculty member.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s bimonthly “Echoes of Memory” program for survivors who volunteer, now marking its 20th year, is many things to many people: a community where those who lived through the Holocaust can connect with others, a space to make meaning of their experiences, and—a writer’s perpetual frenemy—a deadline.

Margaret Polizos Peterson Ph.D. ’14, assistant clinical professor in the College of Education and workshop leader since its start, recalls that in the beginning, most participants were older survivors who had endured ghettos and concentration camps and were determined to ensure that history was written by those who had lived it. Facts, dates, names, who was lost from the family—that’s what they focused on.

Now, as the number of those survivors continues to dwindle and members of a younger generation who were children during the war assume prominence, the urgency of preserving their memories remains, but a more nuanced understanding of their task has emerged: one that recognizes that remembering a traumatic life event is a necessarily subjective project.

“One of the survivors said this great thing which sticks in my mind,” says Peterson. “She said, ‘I don’t write a fact, ever.’ What she meant was, ‘I’m telling my story. I’m telling the experience that I lived.’”

Many survivors still feel the desire to solidify history in writing, says Peterson. But many also feel a more personal mission to tell their grandchildren and great-grandchildren that they were there, and how that felt.

ON A SPRING AFTERNOON, nine Holocaust survivors and I gathered in a video conference to discuss their writing. My own maternal grandparents were born to Jewish families in 1911 and 1917 in Poland. Each survived ghettos and concentration camps with just one brother apiece; the rest of their families died. They wrote down nothing in their lifetimes, but my mother heard enough to know an outline of their histories—inherited knowledge for which my brother and I will one day be entirely responsible.

The survivors were mostly gray- and white-haired, some wearing glasses, sitting amid an array of houseplants, bookshelves and framed art. Many had built up a familial ease after years of attending the workshop together; Gorog shared a photo of his newest granddaughter. One woman summed up her experiences with a disarming nonchalance, one that comes with having shared one’s story many times among a group that can relate: “Nothing terribly special,” she said. “I went to Auschwitz and survived.”

They read aloud the writings that they’d prepared on a pre-assigned theme: something untranslatable. They joked about expressions from their native languages: “Don’t trust the goat with your cabbage” from Hungarian, “You can’t dance with one rear end at two weddings” from Yiddish. Peterson asked frank questions. “How did your mom describe death to you?” she wondered aloud to one survivor.

Peterson describes herself as the ideal kind of person to facilitate these discussions. From her outsider perspective, she can ask for simple details that draw out deeper context in writing.

“I very much try to take the position of a careful reader,” says Peterson. “I’m not their kid, I’m not their contemporary, I’m not Jewish, I’m not a survivor. I’m only a really good reader who wants to know more.”

Twenty years ago, Peterson was a writing instructor at Anne Arundel Community College when her photograph appeared in Annapolis’ Capital Gazette newspaper in a story about a poetry anthology. Soon, an employee of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum called her, asking if she wanted to get involved with a workshop it was launching.

At first, Peterson was unsure, considering herself unqualified. “I knew what a person who has a college degree knows about the Holocaust,” she says. But the Anne Arundel County native knew about writing, having studied poetry as an undergraduate at St. Mary’s College of Maryland and in graduate school at Johns Hopkins.

She also knew that writing could be a means to explore some of life’s most pressing questions. “I wasn’t raised in a religious tradition. So to me, poetry was my first sacred text,” says Peterson. “I was like, ‘These are people questing around for answers to big questions.’”

“

BEGINNING IN earnest in the 1990s, survivors were at the center of an intense effort to capture their testimonies, including at the University of Southern California’s Shoah Foundation, established in 1994 by Steven Spielberg. It now houses more than 54,000 video recordings. The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s collection holds some 25,000 oral testimonies.

Echoes of Memory, inspired by a similar program at Drew University’s Center for Holocaust/Genocide Study in New Jersey, was another way—in addition to video and audio interviews—to ask Washington, D.C.-area survivors about their experiences, says Diane Saltzman, director of survivor affairs at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

What made a writing workshop unique, she says, was that it asked survivors not only to tell their stories, but also to share them with other survivors as they were being captured. “The feedback and the give-and-take doesn’t happen with other forms of testimony,” she says.

[caption id="attachment_26603" align="alignleft" width="300"]

Al Munzer’s family gathered for a meal before being torn apart by war; two sisters who held him as a baby (above right) died at Auschwitz. (Photos courtesy of U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection, gift of Alfred Munzer and Joel Wind)[/caption]Peterson’s early attempts to lead a workshop about such an immense tragedy sometimes failed. “I thought I had to focus in on the most terrible memories,” she says. “It was a beginner’s mistake.” Now, she says, she offers general prompts—on food, holiday traditions, school, family—that allow people to delve deep or go for something lighter. “I put the chicken on the table, they take the piece they want.”

Responses about the untranslatable ran the gamut of emotions. Al Munzer, born in 1941 in the Nazi-occupied Netherlands, recalled the lullaby sung to him by the Indonesian caretaker of the family that sheltered him until he was reunited with his mother after the war. German-born Susan Warsinger mused on the importance of the Yiddish word machatunim, which describes the relationship between a married couple’s two sets of parents.

Peterson’s role, as she sees it, is to “get (the piece of writing) to be able to do what it is trying to do,” she says. “I also tell them, ‘You’re the writer—if you don’t like my idea, don’t do it.’” Each year, writings from the workshop are published both online and in print.

The members of the workshop, which has been meeting virtually since the beginning of the pandemic, note that the relationships they’ve built over the years are a critical component of the program. Theirs is a bond forged by commonalities—discrimination, loss, immigration. “It’s not the same as being a family, but it is a sort of family,” says Halina Peabody. (She noted that the widows and divorcees of the group have a single-women’s club.)

“While we were meeting personally, it was just good to hug each other and talk through life a little bit,” says Gorog. “Unfortunately, some of them are not with us anymore. That’s a tragedy, unfortunately, we have to deal with.”

Peterson has also developed deep attachments with the survivors over the years. Inspired by her work with the group, she wrote her doctoral dissertation on using writing as a way of making meaning of one’s life after the Holocaust. As she talked with the survivors for her project, their connection grew—and so did Peterson’s sometimes-consuming fascination with the Holocaust. Her own son, she says, developed a “real fear” of Nazis as a child when conversations about the genocide spilled over into their home.

Knowing survivors so intimately “makes all this evil, all the badness, closer to home in a way that is depressing and frightening,” Peterson says. “You have experience of loving these people, and you can’t believe that the world could have been so bad.”

SEVENTY-SIX YEARS after the end of World War II, mortality is a constant undertone to any discussion involving Holocaust survivors. It weighs heavily on those in the workshop. “I’m 88 years old. How long have I got?” asks Peabody. “Everybody’s very, very worried about dying.”

The pressing drive to get everything down on paper before it’s too late feels urgent to many. “Whatever we capture, at a certain point, that’s all that we will have,” says Saltzman.

For survivors like Peabody, telling their story is a calling. In 1942, as a 9-year-old, she, her mother and her baby sister boarded a train in Poland carrying papers her mother had bought identifying them as Catholic. The four-day, four-night journey would, Peabody’s mother thought, bring them to a safer location.

On the train, a man pressured Peabody’s mother into revealing that they were Jewish. He told her that when they arrived at their destination, a town called Jarosław, he’d turn them over to the Gestapo. The family waited tensely for the train ride to be over, and when they arrived in Jarosław, the man escorted them off the train. “I started pulling at my mother, saying, ‘I don’t want to die,’” says Peabody.

Her mother appealed to the man, giving him all of her possessions and money, and asking why he’d want their blood on his conscience. He stopped, returned a portion of the money to Peabody’s mother, and let them go, warning that they were likely to face a slower, more painful death elsewhere. (In fact, Peabody’s sister and parents survived the war.)

Today, Peabody knows that time is short, and that only she can tell others her story and the messages it carries. “I feel now it’s an obligation. I need to remind people what happened,” she says. “If I don’t speak up, what does that make me?”[caption id="attachment_26627" align="alignright" width="300"]

Peter Gorog’s father, Arpad, declared dead in Ukraine in 1943, looks at the son who would retain no memory of him. (Photo courtesy of Peter Gorog)[/caption]

The fear of forgetting is a familiar one to me. I can still see my grandfather in his favorite flat cap, carrying the doughnuts he always brought us, but to my young nephew, he will be only a character from photographs and stories. In the end, whether in writing or in memory, only the story remains. TERP

“

0 Comments

Leave a Reply

* indicates a required field