Secrets, Satellites and Howard Stern

From Cold War Derring-do to Sirius Radio, How Robert Briskman M.S. ’61 Helped Build the Foundations of Technologies That Define Modern Life

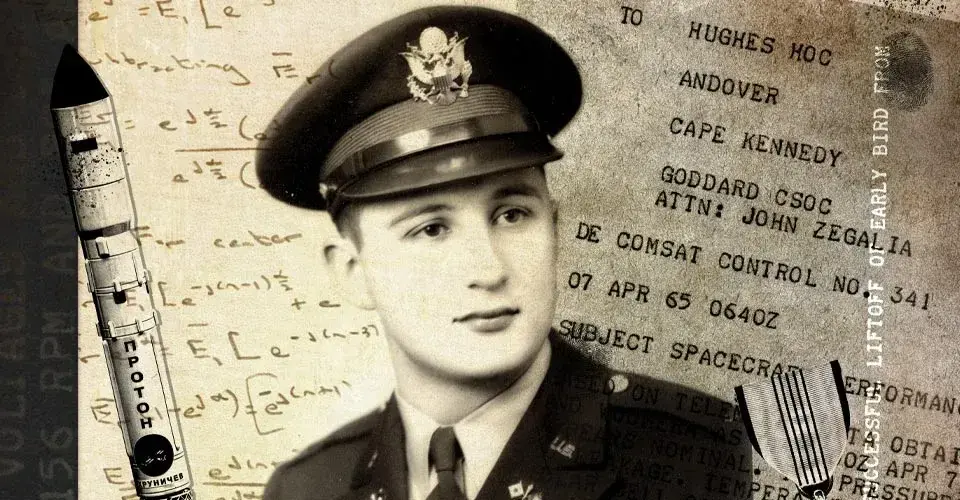

By Chris Carroll | Photo collage by Valerie MorganIn 1956, Rob Briskman sat in a University of Maryland classroom fretting over “a really bad problem.”

The Army signal intelligence officer, back from Cold War clashes with Soviet and other spies in Europe, was in fact struggling with the United States’ really bad problem—one buried in the still-undisclosed arcana of radio frequencies.

While taking graduate classes in electrical engineering at UMD, Briskman was quietly juggling classified work with government agencies developing surveillance and satellite technologies. And now, as the whiz-kid engineer from Princeton listened to Professor Henry Reed discuss UHF wave propagation, his own antenna locked onto something important.

“He was talking about something he had done, and it hit me all of a sudden—you know, I bet I could do that elsewhere,” Briskman says, before adding with a cryptic smile, “And I did.”

Over the broad sweep of Briskman’s lengthy career, he’s taken on many identities: spy, space race pioneer, inventor, businessman. One apt description flows through every phase: innovator.

That classified project sparked at UMD wasn’t his first innovation, but Briskman calls it the key one, an ongoing national secret that paradoxically made him famous in locked rooms where it mattered.

After the military, he was involved in the founding of NASA and the world’s first commercial satellite company, COMSAT; in his next act, he oversaw the development of then unheard-of technologies, like tiny satellite receivers in cars as co-founder of Sirius Satellite Radio. (It’s a feat many users simply experience as their daily, uncensored dose of Howard Stern.)

“Rob has been there for the whole history of satellites,” says Briskman’s friend, business collaborator and technical paper co-author, Joe Foust, vice president of program management for MAXAR, which builds satellites for the company, now known as SiriusXM. “He’s sharp technically, and knows what satellites can and can’t do, but he also knows people. He took something free—radio—that people just took for granted, and improved it, and now people are willing to pay for it. It changed the entertainment industry.”

Now 87, and with the sky above increasingly full of satellites (more than 2,000 at last count, with many more planned), Briskman is on to his fifth act; he’s developing a kind of traffic safety system for increasingly crowded orbits.

“With his accomplishments in satellite communications and space systems, Rob Briskman’s work is woven into the fabric of daily life,” says aerospace engineering Professor Darryll J. Pines, who will become president of the university after more than a decade as dean of the A. James Clark School of Engineering. “The great thing is, nearly six decades after graduating from the Clark School, he’s still turning new ideas into innovation.”

Today, Briskman is supporting innovation at Maryland as a founding donor to the E.A. Fernandez IDEA Factory, now under construction to encourage student creativity and invention. Here are some snapshots—the ones we’re allowed to see, anyway—from a 65-year-and-counting career.

1954-59

“A Bright Young American Engineer”

As Briskman, an engineering major and ROTC member, neared graduation from Princeton in 1954, he says, “I felt like I was being followed.” He was right. He later learned he was being sized up for a classified assignment as a young lieutenant leading an army signals intelligence unit spying mainly on the Soviet missile program. He took command, then transitioned after a few years into a civilian job doing much the same work with the Army Security Agency.

It was more spy-vs.-spy than slide rules and equations. “We were killing people. They were killing us if they could,” he says bluntly.

He can talk, vaguely, about a single declassified mission from that time, when his unit participated in an audacious mission to dig a tunnel into the Soviet-controlled area of Berlin and tap into a communication line. Until its discovery almost a year later, the U.S. and allies could eavesdrop on Eastern bloc communications.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, part of the tunnel has been restored and turned into a museum. “Apparently there’s a cute little plaque that reads, ‘A bright young American engineer realized you could put sensors on the cables and pick up the transmissions,’” says Lenore Briskman, married to Robert Briskman for more than 60 years. “That was him.”

1959-63

Pingpong With Von Braun

Proud as she was of his service to the country, Lenore worried about the gunplay and cloak-and-dagger aspects, and convinced him to move to a newly created government agency: NASA.

Not yet 30 years old, Briskman became the chief of program support for NASA’s Office of Tracking and Data Acquisition. His next challenge came from an unlikely table tennis partner during work breaks: former Nazi rocket scientist and father of the American space program, Wernher von Braun. Briskman had already been working on spacecraft antennae, a forest of them for different radio bands on the Gemini capsule. For a new project von Braun told him it would have to be different. “He said, ‘Rob, have you ever looked at the antennae you put all over Gemini? For Apollo, you’ve got to find a way to use one antenna.”

In response, he developed the Unified S-band System, which combines all the communications, telemetry, command, tracking and video functions into one radio frequency band using one antenna. The military still uses it today.

1964-85

Early Bird and Beyond

Briskman’s next job, starting in 1964, was with the newly established COMSAT, the first commercial satellite company, which operated communications satellites that served the entire world. He was in charge of launching the pioneering INTELSAT 1, or “Early Bird,” in 1965, but what he considers his greatest breakthrough came in the 1970s, as he worked to create the first domestic communications satellite program. Although it’s a persistent issue, radio frequency bandwidth was especially limiting in those days. Briskman, however, developed a new technique known as “satellite transmission cross-polarization”—which allowed a near doubling of transmission capacity, essentially cutting the cost of satellite communication by half.

“Before, satellites were seen as this exotic thing that you would use to communicate across the ocean or around the world,” he says. “But after this, they were practical to use for domestic communications.”

1977

“A Problem With Your Reservation”

While he worked at COMSAT, Briskman’s previous life in military intelligence resurfaced strangely during a 1977 trip to an electronics engineering convention in Moscow.

When the rest of his group checked into the Rossiya, the standard Moscow hotel for Americans, he was told there was a problem with his reservation and sent to a dingy, suspect-looking hotel bugged with microphones. The next morning, a crew-cut Russian firmly escorted him to the airport. Without explanation, he was flown to Siberia, where he was driven to a satellite ground station.

“They handed me a bunch of keys and said, ‘Would you please go through, thoroughly, everything in the station? If there’s a door that doesn’t open, come back to the car, and I’ll take care of it immediately.’”

He did as asked, and was soon delivered back to his conference. He later learned that the United States suspected Russia of violating treaty agreements regarding the station, mistaking it for a missile control facility. “I guess they thought that if I said it was just used for communications, I’d be believed.”

1989-today

“Technically Impossible”

In his Rockville, Md., townhouse (which he and Lenore are selling in preparation for a move to Princeton, N.J.) Briskman fishes out his Android phone and pulls up the SiriusXM app. Although the station’s signature content is Stern’s show, Briskman’s phone is soon pumping out the mid-century strains of the Glenn Miller Orchestra. He credits co-founder David Margolese with the savvy move of lassoing the shock jock for the platform and ensuring listeners would follow. (Another well-known UMD figure, former student and pharmaceutical development CEO Martine Rothblatt, was involved in getting Sirius’s predecessor company rolling.)

Briskman’s role was the technical implementation and operation of the Sirius system. That meant breaking through a number of barriers, from a lack of satellite receivers small enough to work in a car to signals being blocked by structures, terrain and overpasses. From the start, he was told it was impossible. “That’s fighting words for me. It took me seven years to figure it out, but I did it,” he says, gesturing to a wall of patents to his left.

2016-today

Space Jam

An ironic outcome of Briskman’s success: The sky is brimming with satellites, creating new risks. As private space firms make reaching orbit ever cheaper, thousands of new low-orbiting spacecraft could be just a few hundred miles overhead in coming years. The advantage: Compared to traditional communications satellites (which perch in geostationary orbit tens of thousands of miles away), they’re cheaper and exchange signals far more quickly with the ground, enabling new technologies; their rising numbers, however, create an increased likelihood of collision, which could lead to a debris cloud that creates even more risk.

Briskman might just solve the issue with his latest venture, a system that would give satellites the ability to sense and swerve out of the way of space junk.

Seeing the problem clearly and moving decisively to solve it is pure Briskman, says his friend Denis Curtin, a physicist and engineer who worked under Briskman at COMSTAR.

“He’s someone who sees things coming before they get here,” says Curtin, “and then he gets in the middle of it in a big way.” TERP

Awards for a Life of Innovation

In May, Robert Briskman is being named an honorary fellow of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. Among his many other honors and awards:

Member of the National Academy of Engineering; University of Maryland Innovation Hall of Fame, Distinguished Alumni Award and Technology Business Leadership Award; Society of Satellite Professionals International Hall of Fame; International Astronautical Federation Hall of Fame and Fellow; Consumer Electronics Association Hall of Fame; IEEE Life Fellow, Pioneer and Resnick Awards and Centennial Medal; NASA Apollo Achievement Award, Army Commendation Medal.

This story has been corrected to remove an erroneous reference to the Berlin Wall in the 1950s. Construction of the wall began in 1961.

2 Comments

Leave a Reply

* indicates a required field

Jamie Bush

Your headline attracted me to this fascinating article. Its good to know that my own career is owed to this ingenious man. I am a 2000 graduate of UM College of Library and Information Science, as it was known at the time, and currently the Director of Library and Archives for SiriusXM. I have been with SiriusXM since 2008. I am a proud Terp and proud as well to work for a great company like SiriusXM. Thank you Robert Briskman and thanks for this great bio.

Alexander Magoun

As a historian of technology at IEEE, it's great to see Robert Briskman's profile, however redacted, and, just as usefully, that a Terp MLS grad is running XM Sirius's archives. One day, scholars will look forward to exploring that, probably about the same time that various agencies can declassify what Briskman was doing in the 1950s and 1960s. Briskman is also a Life Member of the IEEE who has been deeply involved in various professional activities, and there's a very good oral history with more details of his varied career that he recorded about 18 months ago: https://ethw.org/Oral-History:Robert_Briskman. Alex Magoun '00 Ph.D. American history